Twenty-five years ago, the 27th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified — nearly two centuries after it was written. The improbable story of how that happened starts with the Founding Fathers themselves and winds up at the University of Texas. And it's a heartening reminder of the power of individuals to make real change.

Let's back up to 1982. A 19-year-old college sophomore named Gregory Watson was taking a government class at UT Austin. For the class, he had to write a paper about a governmental process. So he went to the library and started poring over books about the U.S. Constitution — one of his favorite topics.

"I'll never forget this as long as I live," Watson says. "I pull out a book that has within it a chapter of amendments that Congress has sent to the state legislatures, but which not enough state legislatures approved in order to become part of the Constitution. And this one just jumped right out at me."

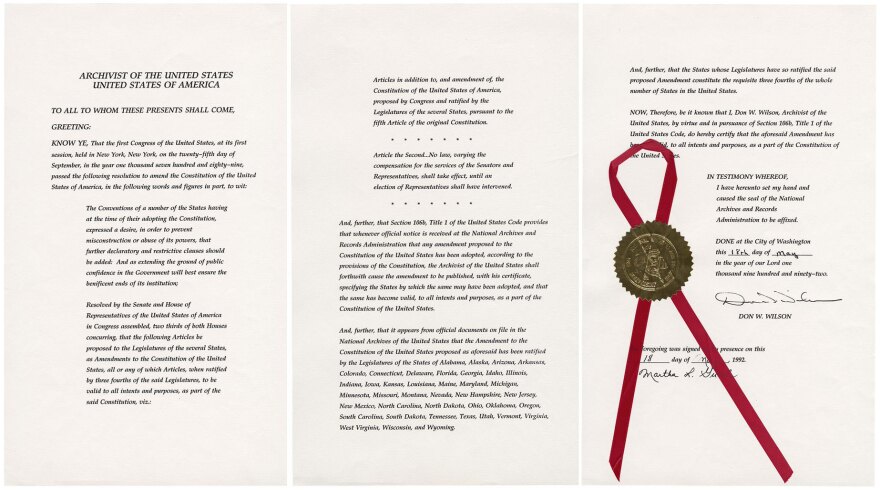

The unratified amendment read as follows:

"No law varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives shall take effect until an election of representatives shall have intervened."

In other words, any raise Congress votes to give itself can't take effect until after the next election, so constituents can decide whether they deserve it.

The amendment had been proposed almost 200 years earlier, in 1789. It was written by James Madison and was intended to be one of the very first constitutional amendments, right along with the Bill of Rights.

But it didn't get passed by enough states at the time. To ratify an amendment, three-quarters of state legislatures need to approve it.

And it turned out that the 200-year-old proposed amendment didn't have a deadline.

Watson was intrigued. He decided to write his paper about the amendment and argue that it was still alive and could be ratified. He turned it in to the teaching assistant for his class — and got it back with a C.

Watson was baffled. He was sure the paper was better than a C.

He appealed the grade to the professor, Sharon Waite.

"I kind of glanced at it, but I didn't see anything that was particularly outstanding about it and I thought the C was probably fine," she recalls.

Most people would have just taken the grade and left it at that. Gregory Watson is not most people.

"So I thought right then and there, 'I'm going to get that thing ratified.' "

Lobbying lawmakers

He needed 38 state legislatures to approve the amendment. Nine states had already approved it, mostly back in the 1790s, so that meant Watson needed 29 more states to ratify it. He wrote letters to members of Congress to see whether they knew of anyone in their home states who might be willing to push the amendment in the state legislature. When he did get a response, it was generally negative. Some said the amendment was too old; some said they just didn't know anyone who'd be willing to help. Mostly, he got no response at all.

But then, a senator from Maine named William Cohen did get back to him. Cohen, who later served as secretary of defense under President Clinton, passed the amendment on to someone back home, who passed it on to someone else, who introduced it in the Maine Legislature. In 1983, state lawmakers passed it.

"So I'm thinking, 'my first success story; this can actually be done'," Watson says.

Feeling emboldened, he started writing to every state lawmaker he thought might be willing to help. He wrote dozens of letters. After a while, it started to work. Colorado passed the amendment in 1984. And then it picked up momentum. Five states in 1985. Three each in 1986, 1987 and 1988. Seven states in 1989 alone.

By 1992, 35 states had passed the amendment. Only three more to go. After 10 years of letter-writing, sweet-talking and shaming, Watson was within reach of his goal.

On May 5, 1992, both Alabama and Missouri passed the amendment. And on May 7, as Watson listened on the phone, the Michigan House of Representatives put it over the top.

His quest was finally over: More than 200 years after it was written, the 27th Amendment was finally ratified.

"I did treat myself to a nice dinner at an expensive restaurant," Watson recalls.

What's so striking about this story is the sheer degree of difficulty of what Gregory Watson did. Amending the Constitution is — by design — incredibly hard to do. In fact, the 27th Amendment is still the most recent amendment to the Constitution.

It turns out that one person really can make a difference.

"I wanted to demonstrate that one extremely dedicated, extremely vocal energetic person could push this through," Watson says. "I think I demonstrated that."

He has kept pursuing these kinds of quests since then. In 1995, he realized Mississippi had never ratified the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. So he pushed that state's Legislature to do it — and it worked. It was symbolic, but it meant something. (Due to a filing error, the ratification was not officially recorded until 2013 ... but that's another story.)

Making the grade

Back in 1992, as Watson celebrated his achievement with the 27th Amendment, things weren't going as well for his former professor, Sharon Waite. She had moved from Austin back to South Texas in the 10 years since Watson was her student. She tried to get a teaching job down there, with no luck.

"I was feeling sorry I'd spent all those years studying and you know ... nothing!" Waite says.

She would look at all the papers and books and stuff she'd collected over the years getting her master's degree and her doctorate and wondered, "What was it all for?"

Until one day, she got a phone call from someone writing a book about constitutional amendments.

"They said, 'Well did you teach at UT Austin in the early '80s?' and I said, 'Yes I did,' " Waite says. "And then they asked, 'Did you know that one of your students, Gregory Watson, pursued getting this constitutional amendment passed because you gave him a bad grade?' "

Waite was blown away. And in that moment, she felt redeemed.

"Many people have said you never know what kind of effect you're going to have on other people and on the world. And now I'm in my 70s, I've come to believe that's very, very true. And this is when it really hit me because I thought to myself, 'You have, just by making this fellow a grade he didn't like, affected the U.S. Constitution more than any of your fellow professors ever thought about it, and how ironic is that?'"

And with the benefit of hindsight, Waite says, Watson clearly doesn't deserve that C she gave him.

"Goodness, he certainly proved he knew how to work the Constitution and what it meant and how to be politically active," she says. "So, yes, I think he deserves an A after that effort — A-plus!"

And that's exactly what happened.

On March 1, Waite signed a form to officially change Watson's grade. Thirty-five years after Gregory Watson wrote his paper, he finally got his C changed to an A.

This story was originally produced for Pop-Up Magazine.

Copyright 2017 KUT 90.5