If you've been driving on I-35 through Central Austin, you may have noticed tall construction walls going up at certain points along the highway and wondered what's going on behind them.

Those barriers are designed to block the sound of machines digging deep holes called drop shafts for one of the largest tunnel projects in Austin history.

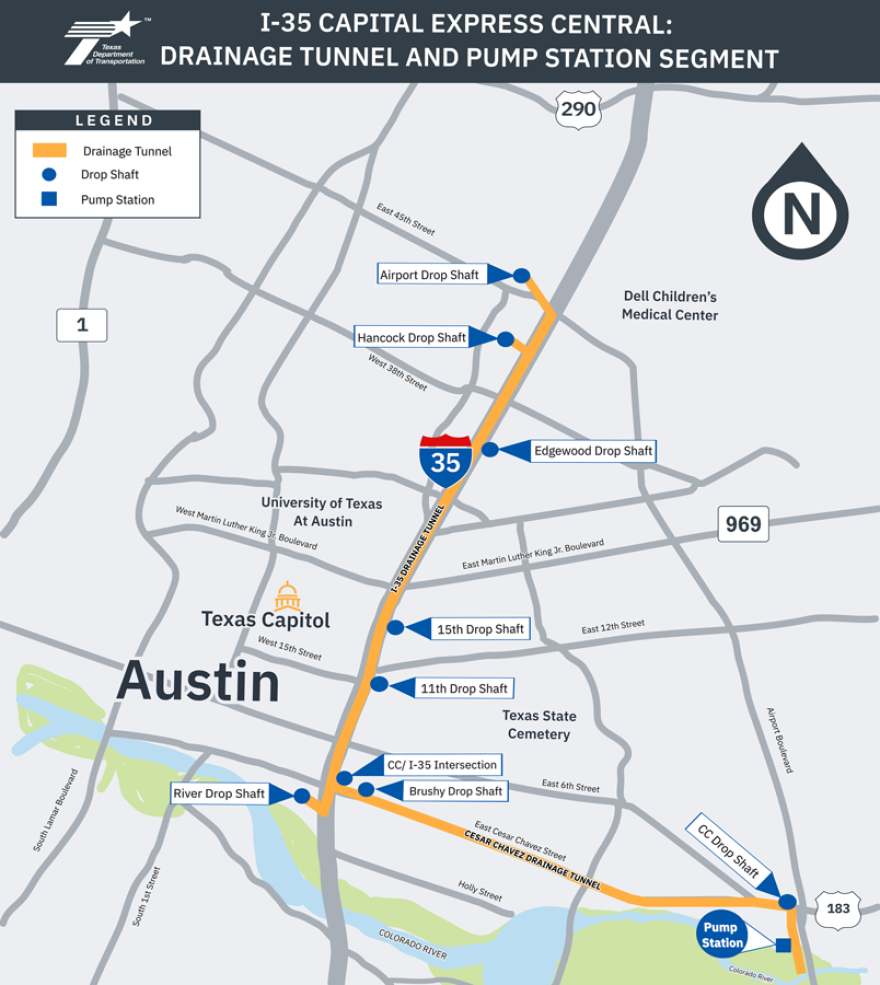

The tunnel is so large that building it will cause the ground to vibrate along its 6.5-mile path down I-35 and East Cesar Chavez Street, creating uncertainty about the risks to nearby structures.

The drainage tunnel is required to prevent I-35 from becoming a raging river during rush hour rains. As part of a major expansion of the highway through Travis County, the Texas Department of Transportation is dropping the main lanes up to 60 feet below ground level from Holly Street to Airport Boulevard.

Those sunken main lanes, parts of which could be covered with giant decks by the city of Austin, will allow a clear view across the highway for the first time since it opened in 1962.

The lowered lanes will also serve as troughs for Austin's notoriously drenching rains when the sky opens up. So the 22-foot-wide tunnel will send that stormwater streaming to the Colorado River downstream of Lady Bird Lake.

In spring 2026, the first of two "double shield" tunnel boring machines will be delivered from Germany. The manufacturer Herrenknecht will send the underground factories in pieces to be assembled on site in Austin.

Like giant robotic earthworms, the German machines will bore the tunnel while simultaneously building its walls with panels of pre-cast concrete. The speed of the machines varies, but they're expected to be able to move up to 50 feet a day.

One machine will start near I-35 at Airport Boulevard and drill south. Another will tunnel west under Cesar Chavez Street from near U.S. 183. The machines, working at a depth of up to 200 feet, will meet near Cesar Chavez and I-35.

Besides the environmental concerns around such a large drainage project — like the air and noise pollution from trucks hauling excavated rocks and dirt 24/7, or routing the waters of Boggy Creek west of I-35 into the drainage tunnel, or pumping thousands of gallons of treated highway runoff into the Colorado River — the construction itself will rattle a lot more than nerves.

"I think it's important to let folks know that outside the right-of-way, they'll probably feel vibrations," said Scott Ford, an environmental supervisor with TxDOT's Austin District.

"The question then becomes, is that feeling going to cause a problem to their structure," Ford said. "You can feel the vibration and it not get close to doing any sort of structural damage."

Historic properties along East Cesar Chavez Street may wind up shaking. Almost 100 of them were constructed before 1930, according to a technical memo by TxDOT. Fourteen of those buildings are more than one story tall and "may need special attention during the construction phase," the memo warned.

The company building the tunnel, SAK and Shea, is supposed to survey the condition of all historic buildings along the tunnel's path before and after construction, watching for signs of damage. An agreement signed by TxDOT and the Texas Historical Commission requires close monitoring of vibration and quick adjustments if the ground is rattling too much.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQ6lz4rcSFA

To better understand what the vibrations might mean for these structures, KUT News asked a leading expert on how underground excavation affects buildings to review some of the project's technical documents. Those documents included a geotechnical baseline report and boring logs of the soil beneath Cesar Chavez.

"People will feel vibration in the same way if there was a big truck running down the road, they might feel it," said Debra Laefer, a civil engineering professor at New York University. "But what we know is it actually takes quite a bit of dynamic action for buildings to move and for them to be damaged. So while it might feel like a lot's going on, the building is probably absorbing it without difficulty."

Still, Laefer said, without conducting a site visit to Austin and inspecting individual properties, it's difficult for her to say anything with certainty. She suggested anyone living nearby prepare to document potential damage to their property.

A bigger risk from vibrations can come from how the soil settles after boring, Laefer said. The slow movement of ground around a tunnel could cause issues ranging from cosmetic problems like hairline cracks in walls to structural damage.

Lighter buildings such as single-family houses tend to put less pressure on the soil, while heavier buildings or large industrial facilities are "almost driving themselves towards the excavation or the tunnel movement," she said.

But Laefer said the geotechnical data she reviewed indicates the ground is "competent," meaning it's dense and well-compacted.

"If you imagine a bag of marbles and everything's kind of tight up against each other, there's less chance for movement," she said. "Whereas if the marbles are kind of moving around, any disruption to that, quite a few things are going to move."

The tunnel's pre-cast concrete liner should also help reduce the risk of soil shifting, she said.

"These would be things that would make me less concerned," Laefer said.

TxDOT says anyone with concerns can reach out to them by leaving a voicemail at (512) 366-3229 or by emailing CapExCentral@txdot.gov.

Before tunneling starts, the public will have a chance to see the machines up close. TxDOT's contract requires SAK and Shea hold two "Touch a Truck" events on Saturdays allowing the public to visit the site, touch the equipment and have any questions answered by experts. Those events are not yet scheduled.

Copyright 2025 KUT News