Watching films and TV, I always admire the oddballs, the abrasive, eccentric ones, the pariahs, the sardonic underdogs. As a teen, while my friends were watching saved by the Bell, I was hanging out with Gomez and Morticia Addams on Cemetery Lane.

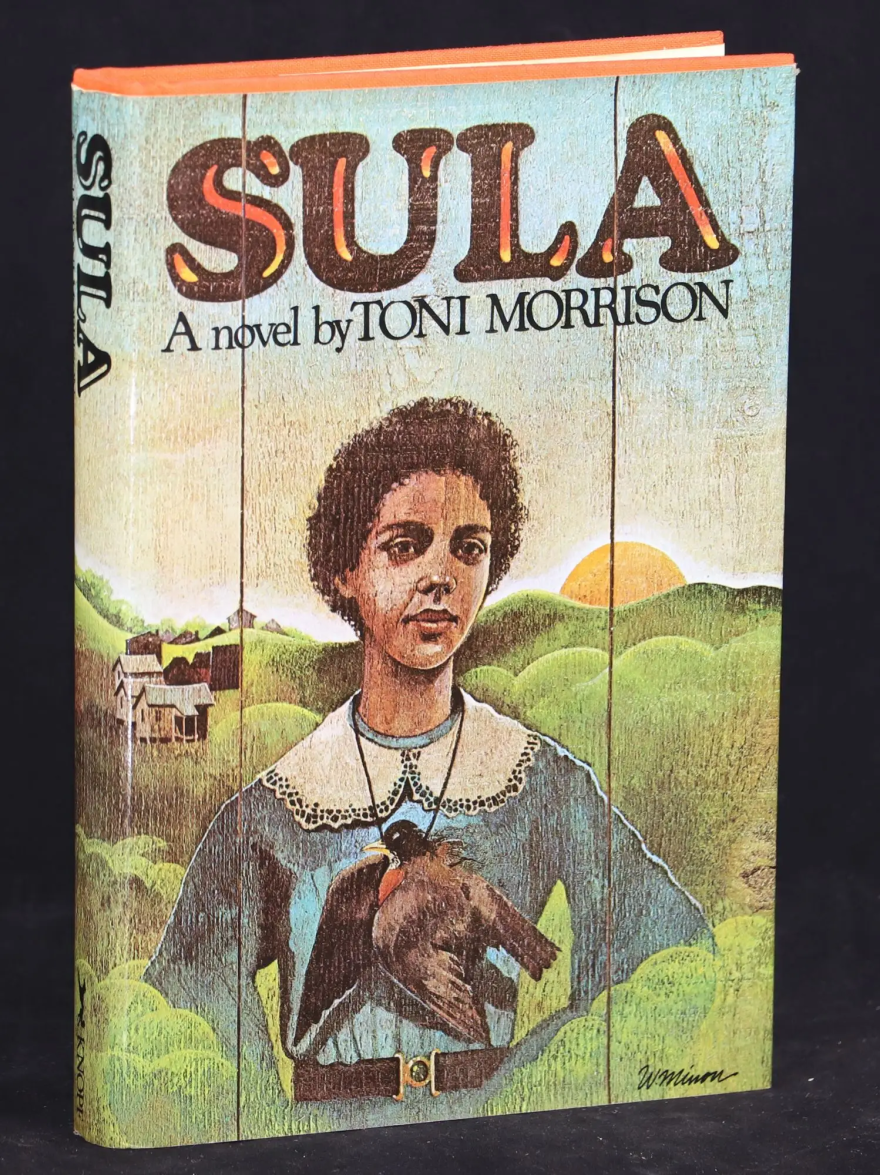

The Zack Morrises of the world never held much appeal for me. But I perceived in Wednesday Addams a kindred spirit to my own. And I think even then I recognize the implicit value of that perennial literary staple, the outcast. Such characters rarely take the spotlight in their respective narratives, especially in novels from the classic and modern eras. But Toni Morrison, in her typical avant-garde approach to literature, decided to give the outcasts center stage in her second novel, 'Sula', published in 1973.

Before her death in 2019. Morrison's subsequent books garnered her many well-deserved awards, most notably including both the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the Nobel Prize in Literature for the Truly heartbreaking novel 'Beloved'. However, the simple story of strange Sula Peace and her stagnant, intolerant black community remains Morrison's greatest artistic triumph. In my estimation.

Sula spends her turbulent and tragic childhood in the bottom, where she endures the deaths by fire of both her uncle Plumb and her mother, Hannah.

The aggressive distrust of her grandmother Eva, and the sorrow of the accidental drowning of Chicken Little. A little boy Sula playfully throws in the local river, who never resurfaces her best friend.

Through all this trauma. Nell Wright later marries the dissatisfied Jude Greene, replacing Sula's friendship with a fragile and ultimately unfulfilling marriage. When Sula later returns to the bottom after a decade's absence, she swoops into town with an escort of Robins. With so many of the emblematic birds of Spring that the locals call it a plague.

Thereafter, Sula institutes some hurtful, though much needed change in the bottom; relegating her disturbed grandmother to the nursing home, breaking up Nell and Jude's marriage through adultery, and serving as the community's chief scapegoat and its catalyst for ethical improvement. Brilliantly, Morrison has rendered in Sula an honest exploration of how characters and real people like Sula Peace serve an indispensable purpose within the tribal groups we so often inhabit in our desire to be approved and accepted.

Namely, Sula and her fellow nonconformists force their disapproving neighbors to weigh the true worth of their assumed beliefs and shared values against a common outsider, the one whose alternate perspective illuminates through contrast the relative soundness of each society's tacit moral code. For example, in The Breakfast Club, when Claire tells Bender she hates him, that teenage outcast who catalyzes and transforms his small group into something better, replies simply, "Yeah? Good."

Such figures expose the flaws in our reasoning, the poor assumptions we make about ourselves and others. Like the irritating grains of sand that create perfect pearls, outcasts like Wednesday, Bender, and Sula just make us better, more honest people than we were.